LFN's Submission to Scottish Government Human Rights Consultation

Last month, we submitted a response to the Scottish Government’s consultation on ‘A Human Rights Bill for Scotland' to emphasise the importance of taking an ecological approach to the Right to a Healthy Environment, and to highlight the role that Rights of Nature can have in realising this. In short: if elements of nature are not directly protected, the healthy environment for humans will continue to be devastated.

The Scottish Government’s proposals seek to incorporate human rights norms from international human rights treaties into Scottish law – and this includes establishing the (human) Right to a Healthy Environment (RtHE) as a stand-alone right in Scottish law. This is an exciting development, and a necessary one, because while this right has been recognised internationally, it is not part of the existing European Convention on Human Rights or UK Human Rights Act.

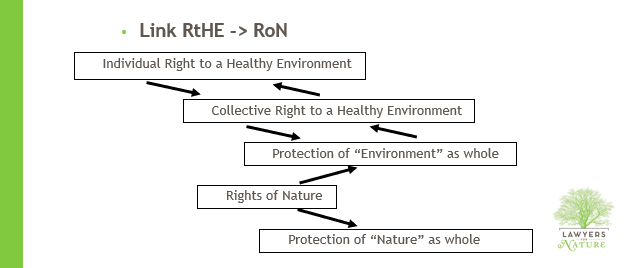

The traditional approach to human rights is based on a false conception of humans as atomised individuals abstracted from social or ecological context. The recognition of the RtHE moves us towards a legal notion of humans as existing in an ecological world, and that if it is not healthy, we face a vast range of problems. Yet the individualistic liberal approach to human rights, even as it expands to recognise the need for a healthy environment, fails to recognise the relational socio-ecological context which individuals live within.

Establishing the Right to a Healthy Environment is a step forward. But in our submission, we argued that if an ecological approach to the RtHE is not taken, it will be unlikely to achieve the goal of securing a healthy environment into the future. We recommended that the Scottish Government draw from global best practice and adopt the collective and ecological approach to the RtHE which has been developed in Latin America.

Our submission included:

- The recognition that “All human rights ultimately depend on a healthy biosphere. Without healthy, functioning ecosystems, which depend on healthy biodiversity, there would be no clean air to breathe, safe water to drink or nutritious food to eat.” [Report by David Boyd as Special Rapporteur, A/75/161, paragraph 3]

- That the notion of a ‘healthy environment’ should be understood as whether it is healthy for all life, in a good ecological state. An understanding premised only on whether the environment is healthy to humans is short-sighted: ecological degradation may not cause immediate harm to humans but in the future undermines the necessary foundation which supports human well-being and flourishing.

- The need to have a collective dimension to the right, not just an individual one. In the words of the Inter-American Court on Human Rights: “In its collective dimension, the right to a healthy environment constitutes a universal value that is owed to both present and future generations. … the right to a healthy environment also has an individual dimension insofar as its violation may have a direct and an indirect impact on the individual owing to its connectivity to other rights. … Environmental degradation may cause irreparable harm to human beings; thus, a healthy environment is a fundamental right for the existence of humankind.” [Inter-Am Ct HR Advisory Opinion OC-23/17 at 59]

- The ecological strand to the Right, which recognises the need to protect the natural environment directly and immediately even where there is not a specific violation of an individual human right. This is necessary to preserve a healthy environment before it gets degraded to a state which causes harm to human health. This strand of the RtHE has been recognised by the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court, in Colombia, Ecuador and Mexico.

- We also invited the Scottish Government to consider that, given that the environment must be protected holistically and directly in and of itself, Rights of Nature laws are a method of achieving this protection which should be further explored. The close interconnection of these two approaches has been recognised in the Latin American jurisprudence.

There is little difference between securing a healthy environment for humans and securing ecological integrity for a healthy natural world. An approach which does not protect the natural world directly, and only has the strand of the individual human right to a healthy environment, is unlikely to achieve this protection into the future. This was the view taken by the Irish Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss, who recommended the inclusion of both the human right to a healthy environment and Rights of Nature in the Irish Constitution (more here).

Our submission can be read in full here:

Thanks to LFN volunteer Hannah Taylor for research assistance in relation to our submission.