From Nature Aware to Nature Positive Business

LFN’s Alex May reflects on developments in relation to business and nature, in light of the recently published Opinion on Nature-related risks and directors’ duties under the law of England and Wales.

We are in the midst of a huge shift in terms of how nature is considered in business. Even a decade ago, it was barely being discussed; now, it is mainstream. In the view of the recent Opinion on Nature-related risks and directors’ duties under the law of England and Wales (‘the Opinion’), which was published earlier this month, consideration of nature-related business risks is a standard part of directors’ duties.

Sadly, this shift is well behind schedule: it was obvious decades ago that we were on a catastrophic trajectory. It’s only happening now because the extent of ecological damage, and the multifaceted effects on human lives, is at a scale that can’t be ignored or denied. Continuing business as usual is a death sentence for both the natural world and for humans who rely on “ecosystem services” to eat, drink, breathe, and have safe places to live.

The emerging norm is now that not considering the ecological entanglements which businesses have would be a failure of legal responsibility. However, though this is groundbreaking, it is vital to move from mere awareness of the entanglements to addressing them. This Opinion sets out the current state of play, but it does not move us closer to the idea that business activity should do no harm or bear some liability for ecological damage. It only means that directors, as part of their duty to promote the success of the company, should be aware of and manage nature-related risks as they would any other type of business risks. A sustainable economy in which ecological destruction is not an inevitable economic by-product is still far away – though there is movement towards this.

The Opinion in Summary

To avoid confusion for lay readers: the law has not changed and this is not about businesses acting in a way which is more positive (or less negative) towards nature. Instead, the essence of the Opinion is that businesses should be active in managing nature-related risks to the company as part of regular business practice.

The Opinion was commissioned by the climate advisory firm Pollination Group and the Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative (CCLI). As the Opinion noted, “The interaction between companies and nature is a rapidly evolving area” and there is uncertainty as to what exactly is expected of directors (at B.1). The Opinion provides clarity in this respect by answering questions about the relevance of nature-related risks to directors’ duties under English law (and the CCLI have a previous research report about the similarities for climate-related risks in a few commonwealth jurisdictions).

The main takeaways of the Opinion are:

1. The importance of considering Nature-related risks for all companies. As CCLI Trustee Thom Wetzer says, “directors commonly fail to appreciate the severity of these risks and thereby needlessly put their company at risk”. As well as impacts on the natural world, these risks include dependencies – where business operations are in some way dependent on “ecosystem services” and therefore fragile to ecological breakdown and impacts which could have compliance or reputational issues. They also include ‘transition risks’, recognising that there are business risks to lagging behind regulatory or social changes, and ‘systemic risks’ linked to tipping points and cascading effects from the breakdown of ecological systems (or social systems rooted in these).

2. That directors should proactively manage nature-related risks. The Opinion is clear that nature-related risks are part of directors’ legal duties just as any other business risk is. “A director who properly identifies and manages a company’s nature-related risks will generally be promoting the success of the company.” (at 239.1) Failure to do so could mean falling short of the legal standard, such that a director could be liable if they don’t consider nature-related risks.

3. The Opinion advises steps directors should take: actively identify nature-related risks; assess and evaluate the potential harm to the company; consider managing or mitigating these risks; consider the extent of disclosure, whether legal minimum or voluntary further disclosure, recognising increasing standards of transparency; and, of course, document the steps they take (at 239.3).

At many points the Opinion refers to the recommendations made by the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (‘TNFD’), which were published in September 2023. While these are currently a best practice voluntary framework, the authors indicate that, as happened with the previous recommendations on climate-related financial disclosures, these are likely to move from a voluntary framework to being industry or regulatory standard in the near future. Directors are therefore encouraged to adopt it sooner rather than later.

Business in an Ecological World

Though nothing has changed with regard to ecologically damaging business practices, both the Opinion and TNFD recommendations show a hugely significant shift in worldview.

In the past, even just a decade ago, business thinking and practice was rooted almost entirely in the typical western modernity worldview, which considers humans as separate from nature. In this duality, human activity is carved out from the ‘out there’ natural world. This separate natural world is considered to exist for human benefit: land should be economically useful; natural resources converted into commodities for humans; and the world remade as we think benefits us.

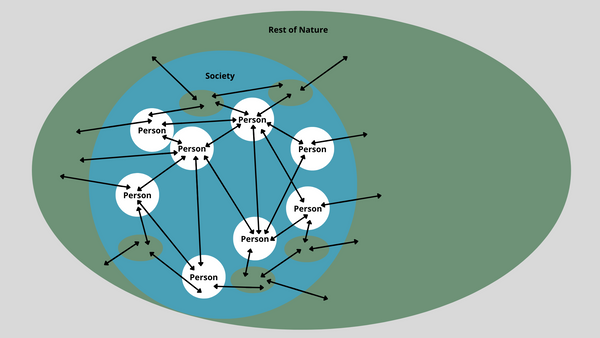

Even without recognising that non-human nature has intrinsic value which humans should respect, this worldview is scientifically defective in not recognising the reality of living in an ecological world. In actuality, humans are part of the natural world; embedded in it, not separate from it. (More on this here.)

That dualistic worldview also comes with hubristic ideas that humans can manage and control the natural world, present in the attempts at technological “solutions” which do not actually address the underlying social causes and cultural drivers. For example, efforts to use market-based systems to internalise harm, such as emissions trading systems, have not worked. These suggestions are made both maliciously and in misguided good faith by those who want to continue business as usual instead of facing up to the necessary change in our attitudes and behaviours.

A similar worldview shift is underway in the human rights space. Traditionally, and in most global north legal systems, human rights happen in this dualistic mode of thinking (which here also includes issues with the abstraction of the conceptual individual from social and economic context, and the way that economic social and cultural rights have been left behind). In the last decade, it has been recognised at the UN level that the Right to a Healthy Environment is a core human right, though it is seldom recognised in anglo-american legal thinking. (For more on the Right to a Healthy Environment, see this blog post.)

The Opinion and the TNFD recommendations mark a shift to an ecological worldview, based in recognition that human activity is embedded in an ecological web of activity. As is said in the TNFD recommendations:

“Our society, economies and financial systems are embedded in nature, not external to it. The prosperity and resilience of our societies and economies depend on the health and resilience of nature and its biodiversity.”

(p7, TNFD recommendations)

The Opinion gives some examples of such nature-related dependencies (at C.2), such as agriculture and food wholesalers facing business difficulties due to declining soil health or invasive species, or business activities affected by flooding and extreme weather events. In short: given that we are in an ecological world, directors should be thinking about doing business in this modality. Being environmentally aware is no longer just corporate social responsibility issue but has become part of core risk management.

It is a deep shame that we have reached this point because ecological damage and collapse poses a problem for business activity, not because of efforts to do the right thing.

From Awareness to Action

Recognising that business happens in an ecological world, and the position of the Opinion that directors should be aware of and manage nature-related dependencies and impacts, is a start. Yet businesses exist primarily to make a profit, and though maximising shareholder returns is not a legal obligation, the financial structures of large corporations are almost always towards that end. What we need are serious changes that move beyond awareness of nature-related business risks and instead towards ensuring that business, society and nature exist in harmony.

Those who are familiar with the nature and business space, or the work of Lawyers for Nature, will be aware that we’ve been supporting a few businesses to align their corporate governance with a nature-positive mission. This is about doing things differently, such as having a board-level nature representative whose role is to internalise the otherwise outside perspective and challenge business as usual.

Discussions around business and ethics are not new. Should businesses be allowed to profit from slave labour in their supply chain? What about land displacement, human rights violations, fossil fuels, or pollution? I would guess that the majority of people would agree that it is not acceptable to profit from evil actions – though of course the tricky question is which actions are evil.

The Opinion recognises that there are business risks in lagging behind social change, termed ‘transition risks’. It describes these as the ‘misalignment of economic actors’ with actions which seek to protect nature, such as regulatory changes, investor sentiment and consumer practices. Fossil fuel companies are an easy example of such a situation, with a huge disconnect between what it would mean to seriously act on climate change and the business plans of energy companies. The Milieudefensie v. Royal Dutch Shell plc case is an example of what this might look like, with Shell being ordered to reduce emissions in line with the Paris Agreement goals as an application of Dutch law’s general duty of care. Though this case is an outlier, as courts tend to leave significant legal realignment to legislative or executive branches of government, it lays bare the size of the gap that currently exists.

The idea that business should be socially positive is growing. The ‘triple bottom line’ approach, that a business should be positive for profit, people and planet, has been around for a while. The B Corporations movement, that businesses should be for social good, continues to expand. B Corporation certification involves external assessment and evaluation of a company’s social and environmental impact and adopts a stakeholder governance approach that the impact of decisions on all of the stakeholders should be considered, not only what is best for the financial success of the company. In the UK, the Better Business Act campaign is pushing for a shift to make businesses legally responsible for being beneficial to workers, customers, communities and the environment, instead of only having ‘regard’ to these stakeholder interests.

Last decade, we saw the extension of human rights norms to business enterprises with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (‘UNGPs’). These establish the norm that business enterprises should respect human rights – though unfortunately the UNGPs are not legally binding, and the Treaty Alliance campaign led by global south countries towards proper regulation of corporate activities against human rights abuses and environmental destruction is ongoing. How much longer until it is widely accepted that businesses should not cause ecological destruction, and requiring businesses to respect Rights of Nature?

The strongest way to ensure a positive outcome is to share power. Intentions, transparency and accountability are significant, but the best way to ensure that there is a positive outcome for stakeholders is to grant power, or at least a voice, to that stakeholder. This could be by including stakeholder representation at the highest level, as Faith in Nature and House of Hackney have done in the UK (you can see Faith in Nature’s 1 year report here). It could also be by transferring some of a company’s shares to a trust with the mission of protecting nature and biodiversity, instead of human owners – an approach which Patagonia took to the fullest.

This is a form of ecological democracy: because we live in an ecological world and humans significantly affect the wider natural world, non-human interests should have a say in how humans do things. Hopefully, not only will we see more companies voluntarily internalising nature representation in their governance practices, but in the near future the legal floor will be raised such that all companies must respect Rights of Nature. If we want our economy as a whole to be in balance with nature, instead of ecologically destructive, these are the sorts of change that are needed.